By: Alex Fleites

Douglas Perez (Villa Clara, 1972) is one of those whimsical artists who think that, more than a job, art is a practice of redemption. And so he wanders around the world, inventing cities in which he would like to live, establishing pleasant dialogues with Cuban lithographers and painters from the 19th century as well as with advertising cartoonists from the Republican era, in an attempt to unravel the past and predict, if that were possible, the present.

His work is reverential, even if here and there satire, burlesque commentary and scathing criticism may percolate. He bows before a cultural tradition in which he tries to insert himself, and reveres every day, in practice, the painter's mission. More than the act of opening windows, his paintings propose an immersion in a deliriously warm world: despite the two-dimensionality of the pieces, they feel penetrable. One can and must make a deep immersion in his work, if one wants to get closer to the essence of the singular being that he is.

Trained in the national system of artistic education, in 1996 he graduated, specializing in Painting, from the Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA), an institution where he also worked as a teacher.

His small personal exhibition Cómo acabar de una vez y por todas con la cultura (How to End Culture Once and for All, Center for the Development of Visual Arts, Havana) dates back to 1995. It is followed, by leaps and bounds, among other interesting exhibitions: Más se perdió en Cuba (Berini Gallery, Barcelona, 1998), Las Flores del mal (Metis Gallery NL Amsterdam, 2003), Two Citizens of Utopia (The 8th Floor, New York, 2012) and El quinto mundo (Breselittle Gallery, London, 2016-2017).

Pieces by Douglas Perez are part of public and private collections in Cuba, the United States, Holland, Spain, Mexico, Belgium, Brazil and England.

In an interview granted to Suset Sanchez you point out as characteristic of an area of Cuban contemporary art, the "choteo", the carnivalization, the parody of what is understood as great art. Do you think this is due to a "third world" complex or to the conviction of the impossibility of producing great art from these latitudes?

Long before I stopped being a painting student at ISA (1996), I was attracted to popular art as a meritorious expression of the most authentic traits of the individual's subjectivity. In the academy they try to train the 'Artist' with a capital 'Artist' by developing muscles of rhetoric and egolatry on steroids, as if he/she had to become a gladiator of the intellect. But in reality I sensed that it was also important to become aware of what it would be like to "take the street" after all that was over, where unsuspected doors would open to also discover what art can be or how it can be practiced. Soon I would discover, experimenting without resting, painting as my approach to reality; that one could interact in a unique zone between high and low culture, and that this was defined as "carnivalization". Despite the fact that Mikhail Bakhtin had distinguished between two opposite, impenetrable and incommunicable worlds: the world of culture and the world of life. There was that desacralization with which I always associated the discourse of figurative painting because of its inevitable pairing with the transcendentalism of tradition and, in turn, its easy comparison with jokes and parody.

El caro norte, 2006. From the series "Polizón", oil on canvas, 70 x100 cm.

The "Third World complex" is a nice and comfortable cliché, like the title of a Wifredo Lam painting. I am not so sure now that it is really so; the truth is that I have always wondered why from here, in "barbarism", there is an apparent contradiction between the exquisite expressions of the discourse and the vulgar compulsion of the word in the social context. I think it has something to do with the insular condition (I see it in Osvaldo Sanchez, Gerardo Mosquera, even Elvia Rosa and Hector Anton...). In the end, great art in Cuba has its starting point there, but I also understand that it is often defined from that self-flagellating perspective. But as you rightly say, that's just a "zone"; one of the many edges of approaching the matter; which is the one I go through.

The porvenir, 2008. From the series "Pictopia", oil on canvas, 80 x 100 cm.

I know we deal with "swampy" concepts when we refer to the art institution. We should ask ourselves, what kind of art are we talking about, what are the legitimization devices of the work we are talking about? Let's say, for instance, does an African artist not reach his greatest consecration until Western critics positively sanction his work? What is consecration for a Cuban artist, how does one reach it?

In my opinion, we should not ignore the fact that the "art institution" is conditioned by certain guidelines or agendas that are in line with its interests, and that these often do not coincide with the personal proposals of the artists; just because the biennials or other contemporary art events of the many that take place in the West wield a thematic axis and are developed under an atmosphere of complete plural acceptance, does not mean that they do not consider certain limitations and categorizations for the art they try to promote. It is clear that the artists' negotiation skills are constantly put to the test here. They are, on the one hand, the ability to perceive, outside of public frameworks and slogans, the real platforms with which to dialogue. And on the other, the ability to elude or not the conversion into "support material" of the great media figures that are the so-called "curators and curators" of today's "art institution".

However, we must not forget that "geographical fatalism is a reality" that weighs like a temporal and financial sword on our intention to achieve the legitimacy of any discourse in the mainstream of Western art. It is alienating, exhausting, haphazard and sometimes futile. But it can be achieved. Only, as we know, the road will be longer and more tortuous from the other side of the southern border.

It is preferable to take it, then, in the manner of the Irishman James Joyce, who revolutionized the fictional narrative of the 20th Century, and charged nothing, or very little, in return; on the contrary, he had to pay, together with his publisher, more than a fine.

In spite of the economic hardships Joyce suffered, the photos show him to be neat, dignified, refusing to accept any difference between life and literature and dedicated to erasing any fictional vestige that might come between the two.

Would this example, perhaps, serve as an optimistic relief for "an international consecration" of Cuban art? I hope so. I belong to that class of Cubans who think they are inexhaustible.

You have used the term "tropical artist" on several occasions. Is the concept yours? Who or what are you referring to?

I spent many years thinking about that idea of the "tropical artist", trying to concretize a way that would allow me to forge a character that would be distinguished by his forms and manners. Whether these were of a social nature, intentionally acquired, or simply the result of the most unpredictable circumstances, such as environmental influence or some kind of historical ethnicity. You see: it turns out that man is not only the result of what he eats, although that is important. He is also the result of what he reads here and there. One afternoon I was in Port of Spain (Trinidad and Tobago) when the idea suddenly appeared for the first time; I had been reading the life of that protean monster Picasso, pioneer, master of painting like no other, and that super Caribbean context allowed me to accommodate myself to the fickle influence of the muses by painting and reading at the same time. There, on that tiny island, people live as if they were waiting for carnivals. I only know that the concept appeared and I began to use it, picturesquely, as something self-referential.

Fronterizos, 2008. From the series "Stowaway", oil on canvas, 120 x160 cm.

Sometimes I use it as an incantation to the fear of mistaking the signs. At other times, with childish sarcasm, to describe the unsuccessful condition of the insular artist... Perhaps it is something I had read and I appropriated it. There is so much ideological outline and written principles that then remain in scattered fragments as a measure of things. I don't think that concept is mine at all, it was already here when I arrived, I just had to perceive it. Remember that without trying to discover a truck wheel on the Havana seawall, the fishing life preserver was invented.

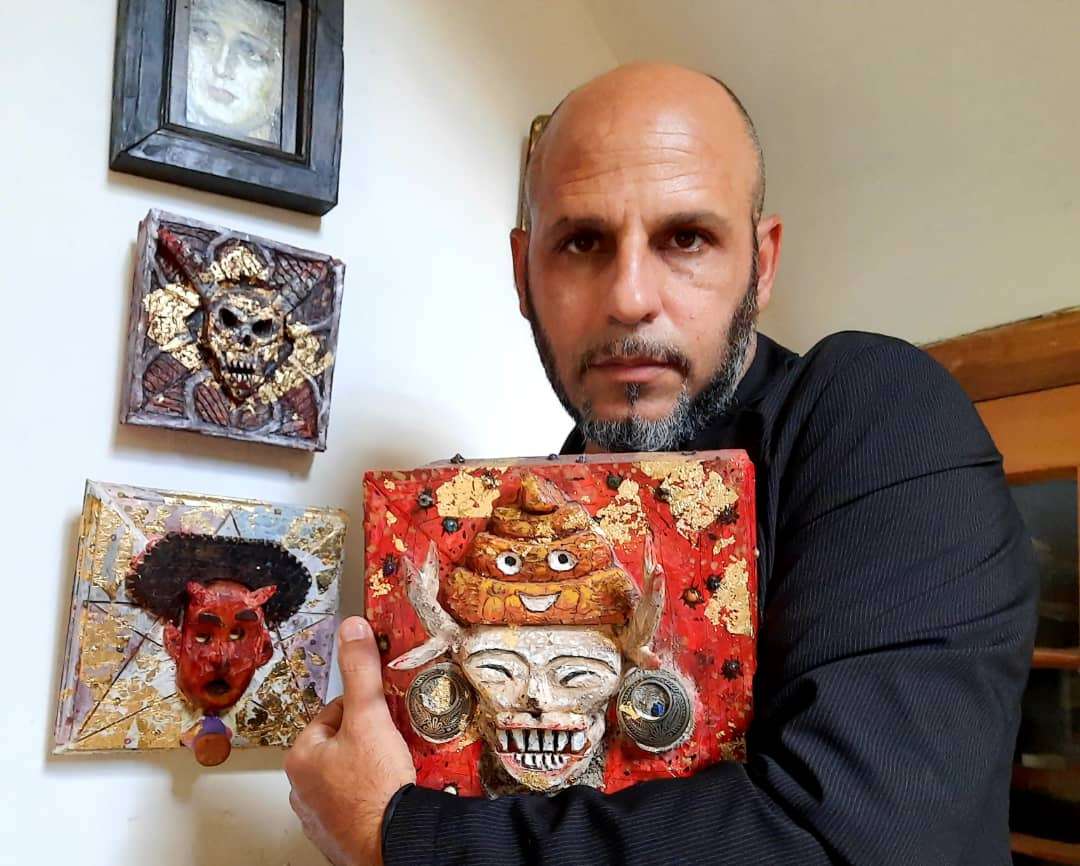

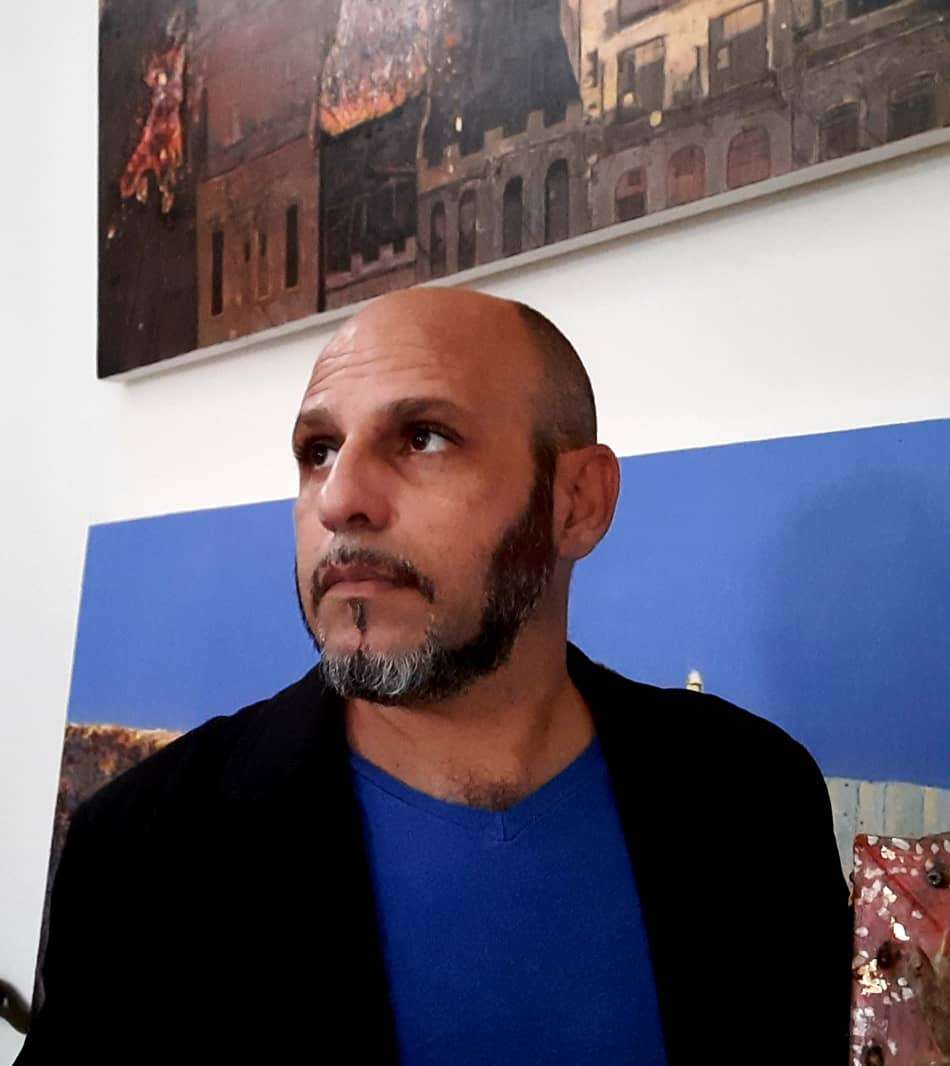

Douglas Perez. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

At a time when communications have made the world less wide and alien, when information flies fast, and an exhibition inaugurated in Tokyo can be attended virtually in real time, are concepts such as national art still valid?

I am not one of those who think that globalization is an expression of participatory democracy. I belong perhaps to the last generation of the twentieth century, a "classic" model already; if we assume the wheel of history with a progressive character, and I have begun to exceed half the accepted "miles" and, therefore, it is confusing for me to glimpse the narrowness of the new universe and the quality of the information it offers. I am probably misreading when I state that the speed of the global world, as seen by millennials, is more of a political construct in which to support certain principles intertwined to pressure the collapse of traditional development policies, and thus favor the resurgence of new infamous factors of domination. I confess that I am not one of those who follow these ideas because I do not feel any pressure to do so. Being a Cuban and having my life experience as a testament, I can confirm that from this side it is not as rosy as globalization appears to be.

Güiro II, 2006. From the series "Stowaway", oil on canvas, 50 x70 cm.

It is from here that I attach great importance to the concept of "national art" as a legitimate way of conquering cultural values for others; revealing the inner being that results from creation, but not as a singular element, since it responds to a logic much more encompassing than the life of an individual, without wanting to sound the alarms for the impertinence of not revering the fathers of aesthetics wrapped in personal sensationalism. I agree more with a generality that encompasses expressions of that nomenclature called low culture, which is what definitely ends up being popular, folkloric, ancestral, traditional or historical art, however it is understood; so many times relegated to the list of national arts. The twentieth century has seen the birth of the avant-garde sedimented in a tireless spirit of experimentation with styles and contents basically elaborated from the conscious recognition of the most local or national art. It is from these bases that the work is then constructed and glorified. Evoked in Henri Matisse's The Dance (1909), where the primitive ritualism of ancient Mediterranean cultures is enlivened, and in Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase, with a whole dynamic more anthropological than artistic, unnoticed by visitors to that exemplary The Armory Show of 1912. The century would not have seen the birth of that avant-gardism without the affectation of previous local discourses. But this also brings with it "the death of art", as the negation of originality and the apex of the eccentric act as a norm. Reducing to the maximum the power to recognize the incidence of the same in contemporaneity. But, come on, tell me if there is not an abundant past spirit in The Monogram, Robert Rauschenberg's sculptural installation, which traps a stuffed wild goat in a fuller tire, on an absurd abstractionism (1955-1959).

As a Cuban artist, I believe that the recognition of these primordial expressions of our culture is vital when conceiving my work, since it has the same impact and energy that Native American art had on Jackson Pollock when he painted that great painting entitled Autumn Rhythm N°30, in 1950.

Ladacar, 2014. From the series "Pictopia", oil on canvas, 160 x 240 cm.

We already know that the artistic work has a symbolic value, how much of this value is intrinsic and how much is added? Can the two be separated? If you had to choose another artist's work to hang in your living room, what parameters would you take into account?

I have a deep respect for the work of art. It is one of the few obsessions in my life. I consider this quality of man (that of producing art) essential for his development in a qualitative way as a superior being as it is attributed. Thus, the dissimilar ways of relating to the works of art are also very interesting, especially from our condition of artist. Somehow always within the expectations is the issue of values that ultimately make us perfect victims of the anxiety for the collectible.

Many times these values are accompanied by our educational background and, therefore, prefigure the degree of interest and importance we give to the works. To be able to discover the presence of a masterpiece or a genius and appreciate it in its totality is complex and very difficult. It seems to me that this is where the meaning of the question comes from. It is clear that for art to somehow fit into our lives it is necessary to let ourselves be carried away by the pleasure of intuition, and by the will to associate it with our despairs of the past and longings of the future. That is how it works for me. Of course, I am not only talking about painting, this is one of the many fine arts; there is a lot of this when, for example, the mental image I have of a country like France, which is universally known, does not include literature or music and if it jumps by definition, the result of the work of three magnificent figures: Charles De Gaulle, Pablo Picasso and Coco Chanel. For their thoughts and works, which always gravitate in my imagination of this European country. Well... and why not? The same thing happens to me with Cuba, where the music of a Caturla has, for me, more weight than a book by Lezama or any other... Anyway, it is something very much given to personal discretion, which is transformed with time. To a great extent, this is what I always try to keep with me when choosing.

I have many works by friends that represent the complexity of friendship and respect, I enjoy basing my criteria on the exchange of works, in this case paintings, photographs and books with colleagues in the profession, and it is basically what I take most into account at the time of living with these works and thus lavish them with a spiritual affection that is beyond mere fraternization and solidary embrace. Never pay money. Enough of paying tribute to those idle bishops and kings. Long live art!

Your work proposes diverse strategies of representation, although it is recognizable by the desire to dialogue with a precedent, which can come from pop art, commercial graphics or the so-called high culture. How would you define your poetics?

There is always something that I feel is wrong with the classification of my work when it is placed in different representational stages, when in truth I try to base everything I do, except the verbal discourse with which I explain the work, on painting. The art of painting in the most traditional way that this category exists, and I do not feel any kind of discomfort about it. Artists, gallery owners and collectors who have appreciated my work over the years up to the present have had the same vision. I have a feeling that perhaps future generations will look at my work as something that needs to be "fixed", for all the problems I may be creating now. But for me the most challenging part of my work, for some time now, is in resolving the conflict between the enormous new global audience that exists and to which I can aspire thanks to how easy it is to disseminate the work on the technological platforms that exist to circulate information, and the possible detriment in gaining acceptance and applause from the traditional elite that consumes, understands and sees my work as Cuban art.

Spoiled, 2006. From the series "Stowaway", oil on canvas, 70 x100 cm.

It can no longer be hidden for artists in Cuba that it is necessary to somehow seek access to that group of influential people who direct and lead museums, galleries, auction houses and publications on art, in order to exist in paradise as a "tropical artist", applying yourself thoroughly and not necessarily being the best of painters, you just have to know how to show off your most fun and daring plumage to have the right to exist..... They are the ones that will define your poetics in the long run and what I think in that sense is not relevant, it is just a mere attempt of definition.

Douglas Perez. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

But it is interesting to see if the pleasure and satisfaction to be felt would be very different, if you suddenly manage to escape from that "establishment" of proud art critics, who will not endorse your work and, consequently, there would be no dealers and collectors for whom you are charming, and you find yourself sinking into oblivion and self-pity; to see you suddenly emerge with cheers of glory in the favorable critical consensus of legions of thousands of instagram likes, YouTube followers and admirers who know little or nothing of the existence of one-world rules for art. Frankly, it won't make any difference. So I don't waste time trying to define my creative poetics. Because it depends on who it appeals to... It's for whoever pays the most attention.

The loneliness of the sniper, 2015. From the series "Pictopia", oil on canvas, 160 x 240 cm.

It is more interesting, then, to contribute with your artistic vision some inspiration to an audience that will ultimately be called to be the builder of the future, and that your work alone is the cement that binds, although not the cornerstone of that construction.

I have the perception that you don't improvise in front of the blank space, that the execution of the work (almost always inserted in a series) is preceded by a well-defined idea. Can you talk about your artistic "kitchen", your procedures, the path that leads you to the finished piece?

I am fascinated by two things: historical literature and the history of painting. All my production gravitates in this orbit, although apparently there are differences between series. As you rightly say, I don't improvise much; I spend a lot of time constructing associations of all kinds and narrating possible obituaries for each piece. Yes, because each painting, once finished, has undergone a delicious death: I kill approximately two every month. In the end the work just falls in the line I have previously sought, in the existing repertoire within that "eternal return" that is culture...to illustrate it. When I face a Goya or a Franz Hals in a museum, I see painting more than anything else and I try to understand the light achieved in the bodies by these artists. I understand that it is a mark on them, something that defines them as immortal; also in Velazquez and Rubens, the light hitting the face of some saint executed by them, one can reason that the painting is applied quickly and dynamically, in a very short time. Maybe minutes... Opposed to Gauguin, who executed painting with an extreme rational methodology that takes months, even years; he believed in planning all the parts of the painting, his light is constructed in a scientific way and with significant licenses.

Bad Thinking, 2015. From the series "Pictopia", oil on canvas, 160 x 240 cm.

I pay particular attention to this when I execute my work, I am careful not to let the referent behave with evident presence in each project, as not to accept that in the freedom of the way of staining and painting The Lion Hunt, a Delacroix, was not equally exalted by the inquisitive gaze of a young Van Gogh, who later also made his attempt. I am sure he did not overlook it either. And thus completes that cycle that determines how something so different in appearance is related as not to become predictable.

And it's funny how very few people dwell on this when they approach my painting, if it carries such resounding weight throughout the process; one of the things most painters do is look at painting rather than appreciate it. People imagine too many things.

Let's move on to genealogy: where do you come from, artistically speaking? What are those paradigms consciously assumed and which ones do you discover a posteriori as part of the permeability to which every artist is subjected as a social entity?

I don't assume myself as such an uneasy being, I think I'm rather from the generation that came up talking all the time; and praising the 80's generation of Cuban art. Those were not people who made art. Rather, they were many monsters or cemíes to idolize, of energies that by worshiping them you became a powerful mystique; there were many and there was enough for everyone. Feeding a mythology that practically in my case was vital. Flavio, Bedia and Carlos Rodríguez Cárdenas had a great influence on me. That is precisely why I am a painter and not a text illustrator or graphic designer, without being misunderstood. It is so difficult to make painting a profession from which to live happily, because of the uncertainty you will always be facing... And when you see in Cuban visual arts the attractiveness of the history of that generation so prodigal in discourses and themes and, at the same time, so defiant in its particular history of dissent and migrations, you then point out like that journalist from Art News magazine: "Everybody wants to get on Van Gogh's boat to be famous after death!". Many of them preferred a raft to begin their difficult journey and leave the island, proclaiming that there is no journey in the plastic arts, no matter how horrible it may be, that professes contempt for misfortune. The idea of genius enslaved by hardship and suffering as the only possible way to achieve a powerful work. That is the delightful legacy of this story, even if it sounds like romantic nonsense. So you have to give full credit to the life of the "disoriented" Dutchman for putting this legend into the orbit of universal recognition.

That is my genealogy, that of contagion (that is the title of a painting of mine from 1994). I belong to the generation that came after, not to deny the previous one or to banish it, but rather to enjoy it, with love.

Although I run the risk of you answering me "the last one, the one I am still working on", I would like you to tell me in which of your many series you think you have achieved in a more effective way the proposed objectives.

The fact is that I don't set out to meet any objectives. My work develops along with my personal interest in the reality of Cuba. I do it without discriminating whatever the result of the content that is created in each of these series. My methodology is to investigate and then poetically interpret everything assimilated, and the experience that each painting leaves is what I strictly value. It is not that I try with my painting to offer a holy remedy or a miraculous cure for the many problems we have; I am not so naive. With my painting, what I do is to take the bow and arrow, shoot, and where the arrow hits, draw a target around it. In this way I always hit the target.

I would like each of my projects to have as that "target" built; to create cultural values, experiences, and contribute to the social development of this archipelago. Although, to tell the truth, I am not entirely clear about what is really created with my painting.

The concept of "gentrification" is still controversial. You have dedicated a remarkable series to this topic. Some understand it as development and others as class displacement. What is your position on the subject?

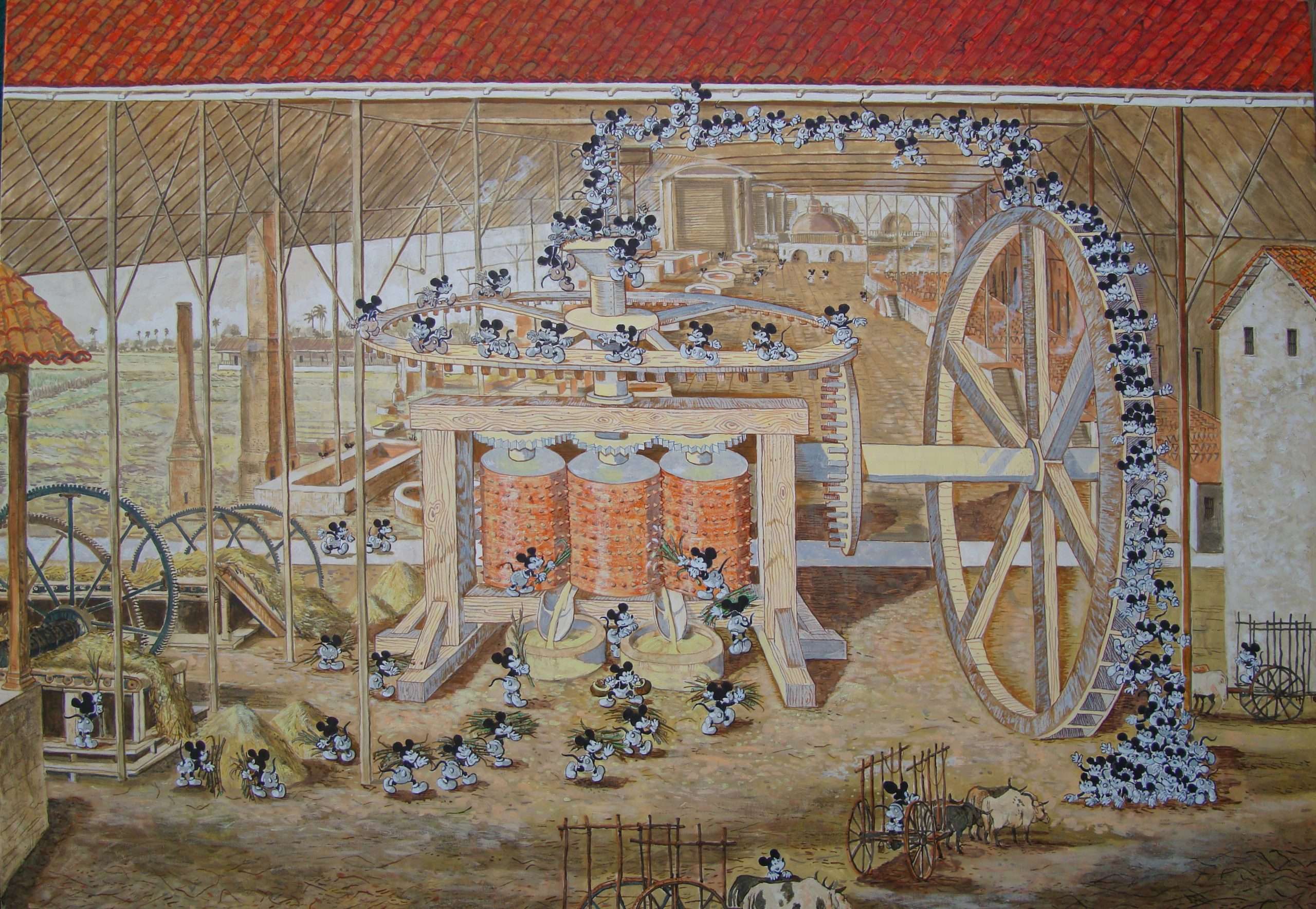

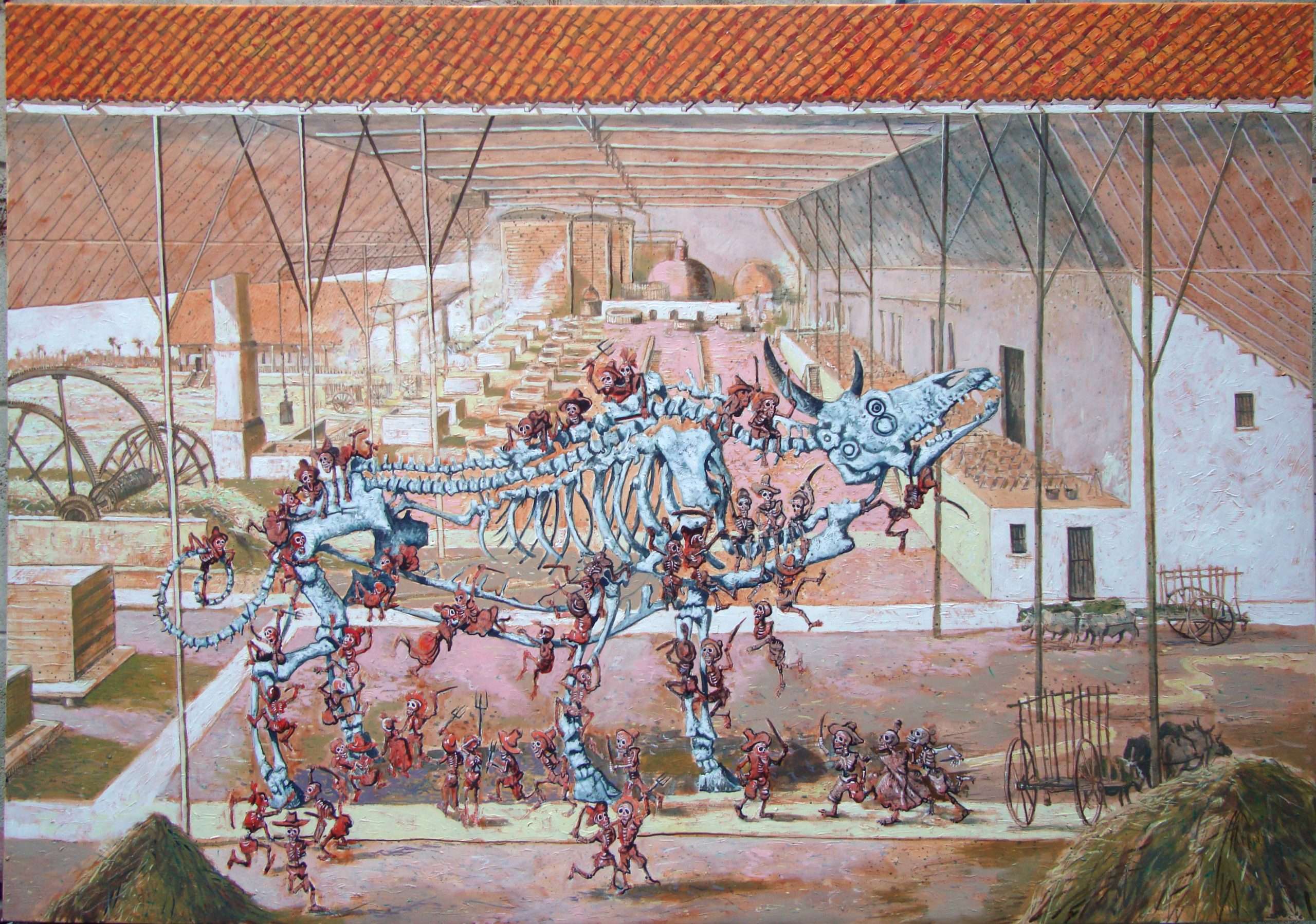

I consider myself a progressive man in the broad sense of the term. In that series I became interested in the idea of displacement and the conversion and substitution of the functions of places; which is how I read gentrification. For many years I have been painting sugar mills, which for me are more the representation of human sugar factories than of sugar itself. I have reflected the socio-political reality of Cuba where the factory stages the country in its complexities and, at the same time, I pay a well-deserved personal tribute to the work of Eduardo Laplante and the costumbristas of the 19th century, which I like so much. However, there are moments when the series becomes critical of itself, and ideas and comments appear that have more to do with the art world; that is where the group of works you point out is inserted. Over time I have become convinced that in the tradition of criticizing the institution, artists are like monkey wrenches; they put pressure on the development of that world.

I see similarities in the way art spaces operate today, especially in times of severe economic crisis aggravated by the pandemic, and the way in which in Cuba buildings and constructions have been redirected to different purposes, away from the functions for which they were conceived, almost always forced by necessity. Some contemporary art agencies in large Western cities have ended up as platforms for relaxation groups and yoga practices or natural healing centers.

Dead Time, 2018. From the series "Gentrification", oil on canvas, 120 x 160 cm.

Dreamers, 2018. From the series "Gentrification", oil on canvas, 120 x 160 cm.

Silly symphony, 2018. From the series "Gentrification", oil on canvas, 120 x 160 cm.

Somehow the displacement of functions is one of the most distinguishable tools that art has, where the morality of the intentions and the political impact of the same is not questioned. They have the same weight to turn a gallery (Sach Feuer) into a blood donation bank in support of public health, as Kate Levant did in 2011 in Chelsea, and to hand out cocaine stripes on a tray to the unsuspecting audience of an artistic performance in Colombia (Tania Bruguera). A new art institution is being built. My paintings consciously avoid falling into any kind of "explicit activism", just as I am not interested in any form of social practice. My art is focused on describing rather the functions of the artistic work from the language of traditional painting, adapted to the needs of the present.

The Pictopia series, which I like very much, raises a doubt: What is it about, the necessary utopia for some, or the total dystopia to which a world as convulsed as ours tends to be?

This series is in line with my compulsive taste for popular culture. For thirty years I have been a fan of Science Fiction literature and movies. I find it delightful to be able to imagine a city as imperfect, underdeveloped and dirty as Havana starring in a journey through time towards a luminous future expressed in whimsical representations.

The ridge, 2013. From the series "Pictopia", oil on canvas, 180 x 150 cm.

For the Pictopia series, I am inspired by the combined reading of a novel by Aldous Huxley (Brave New World, 1932) and another by Orwell (1984, 1949), with a review of the film Metropolis (Fritz Lang, 1927). I take at random, from one and the other literary work, long paragraphs and contrast them with scenes and sequences from the film, in a sort of visual comparison. For years I have been painting these landscapes of Lego structures and failed perspective of the city in which I live.

I always remember asking myself these questions: How is it possible that someone who calls himself a leftist and against British colonial imperialism can describe his own living environment as the perfect nemesis of his existence, as if it were at odds with his ideology? Is the radical left so decadent that it executes in its ideal project of society its own destruction? I have to see if it is possible to create a landscape that celebrates the beauty of a hostile environment and if that will help at all. Therefore, the doubt is valid.

And so time has passed and works from this series continue to emerge, until they form a vast catalog. There, emblematic places of the rich character that Havana can become are reflected in large oil-painted pictures; they are like antidotes to the irrational architecture that generates bad taste and chaos. I want this city to also have the charm of Venice. All these things and more is what I am really after: to be able to transport you from that imaginary to another place that painting brings to the present. Even if the buildings were erected three or four hundred years ago; conservation is a practice that painters are familiar with. You mention "the total dystopia to which a world as convulsed as ours tends". Some time ago I read a science fiction story, in which entropy was inverted through a technological artifice created by human civilization and, consequently, a logic of chaos appeared in some cosmic way, a metaphysical balance, another equilibrium with total loss of the notion of god. I mention it because optimism is part of the humanist tradition in which I have been educated, particularly I express it not from the anthropocentric perspective that sees man as a superior being in his manifest destiny, which is that chronological invocation expressed in what we call the "History of Man", but in the inclusive and tolerant form of the vision of Stanislaw Lem, who is the Polish author of the story I mentioned before: Where there is no exclusion of any kind and man is happy in the country where satire is part of historical freedom as well.

I am one of those who see the great contribution to the game of Cuban ballplayers in the major leagues of the United States. To use a baseball expression that we Cubans like so much, despite the fact that the debacle of the national sport seems inevitable: the ball is white and has one hundred and eight seams for everyone.

Taken from Oncubanews